Life Is Intense From Moment One: Minneapolis Artist Katelyn Farstad

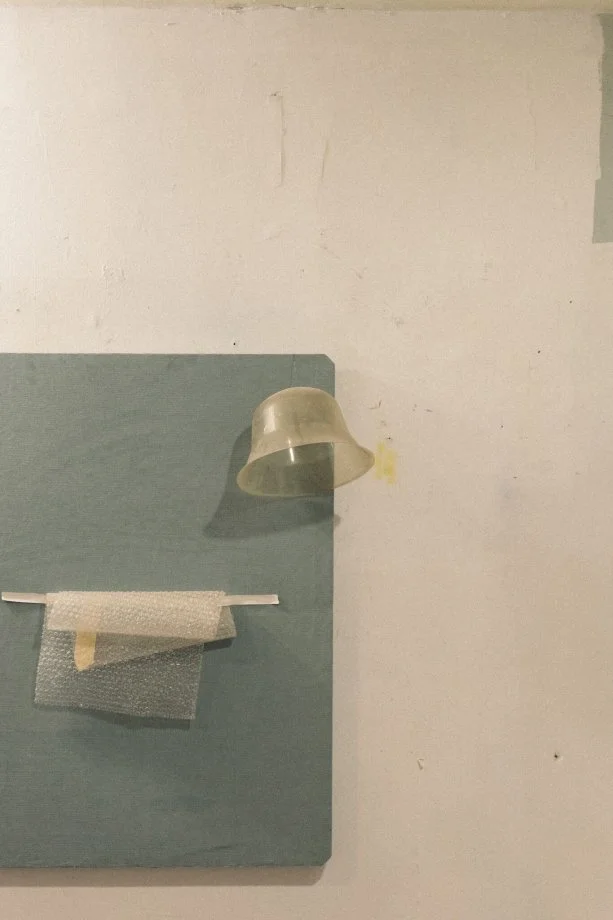

Orthodontic molds, Technicolor Easter eggs, scrawled graphite, broken toys. It’s hard to talk about the work of Minneapolis artist Katelyn Farstad without talking about the anarchic range of her materials and what they suggest about the mind that assembled them.And that doesn’t just go for her sculptural work. Whether she’s collaging photographs of Bichon Frises or layering synth on drums on vocoder drones to create otherworldly experimental music (see her band, Larry Wish & His Guys, and her solo project, Itch Princess), or gathering work to display in GAS, the “metaphysical gallery” she curates, Farstad is, first and foremost, a collector.But put all those things together and you’ll find you have something more than an attic full of thrift-store flotsam and a basement full of guitar cables. You have a singular artist whose work captures the psychic turbulence of being a sensitive person in the world.Have you always wanted to be an artist?Yes. As soon as I discovered art and music I knew that I wanted to try my best to not outgrow it, but really grow into it. I always pictured being really old, thrashin’ on the drums, in an elderly hardcore band. My friend Sam Cramer and I are going to start a band called P.A.P.W.A.D.O.T when we are 75. The name is super dirty, and I wouldn’t even dare write it all out.It seems like your work is often the result of a process of accumulation—Including your visual art as well as your work as a musician, a video artist and your work as a writer. How do you find your materials?The objects I use come from a variety of places: thrift stores, alleys, friends giving me things. Most of the time I have no idea what I am doing—I love color, texture and form. I love sounds and words. I think of it as knocking it out, never stripping it down. I am not sure why I have that tendency. Maybe it has something to do with the attitude of working with what you happen to have, or with what happens to find you. Or not judging what you are doing while you are doing it. When I make artwork or songs, it feels playful, meditative and illuminating. Maybe even a bit like a ghostly purging.Where do you make your work?My art studio is in an attic. It is a bright, messy and crowded place full of everything I have made in the last eight years. My music studio is in the basement, which is neat and packed into a small space. I like to think about that in terms of the cerebral openness of my artwork and the more compressed intimacy of recording music—highs and lows.You utilize many images of children and youth art supplies in your work—polymer clay, construction paper and foam clocks to learn about time-telling. What draws you to that imagery?I think about my own relationship to art and how it started at a very young age—how I enjoyed cutting colored shapes out of paper, rubbing paint with my hands or painting an acorn with glitter. Being a child represents the time in life when you are more in touch with how you feel and not worried so much about how it makes you look.I love clip art, and I have this great medical clip art book from the 1950s with line drawings of a doctor holding up a newborn baby by the heels. It’s featured in one of my pieces. The piece is called “Slap To Life, Slap To Reality” because you get slapped the second you escape your mother. Life is intense from moment one. And that image—everyone can relate to it.You’ve recently secured gallery representation at Luis Campana in Germany, and you’re also a Minnesotan, born and raised, still living in the Midwest. What’s it like being a fine artist in a city like Minneapolis? Being an artist in Minneapolis is great, but also terrible, like I imagine it is for artists everywhere. It is affordable, and I have the ability to work and experiment outside the pressures of commercial success. That is a joke which is also true.I think there is a really unique flavor in Minneapolis that is a cross between grocery store sushi and a tater-tot dish that allows everyone the time and space to actually make interesting work. It is the showing and sharing of that work that is more difficult. And the supporting yourself on art or music—that is very difficult. So, we share and show it to each other. And, I mean, I could always move. But I like it here.I want to ask you about sincerity. Your work occurs largely in a non-mimetic space, using materials and sounds that might feel ironic or a little snarky, or maybe deliberately weird to a certain kind of viewer or listener. But there’s something deeply sincere and certainly emotional about it, too. How do you negotiate that balance?I feel that irony and snarkiness are two of the main ingredients of sincerity. To be free from hypocrisy, one must admit they are a hypocrite. I feel it is good to work within that grey, ambidextrous psychological space, because it represents the futility of attempting to defend a subject like sincerity, which does not need to be synonymous with seriousness. You can be serious and playful all in the same room. This story originally appeared in ALIVE Issue 1, 2018. Purchase Issue 1 and become an ALIVE subscriber.Photo credit: Attilio D’Agostino.