Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of the MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

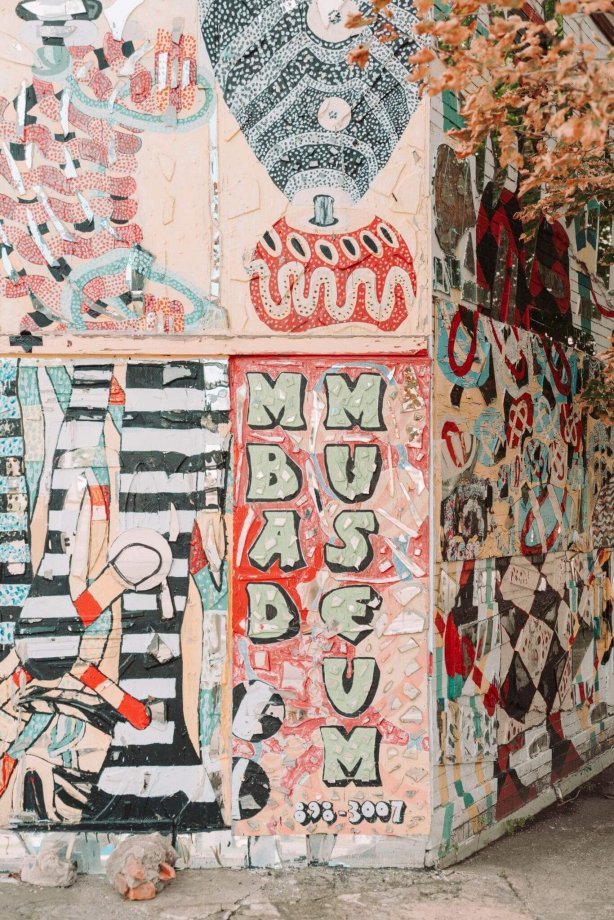

Detroit’s MBad African Bead Museum is part public art installation and part handmade craft showpiece; part sculpture park and part artifact exhibition. Spread across nearly an entire city block just down the street from the world-famous Motown Museum and a few miles from the city’s riverfront, the museum glistens brightly on its street corner.

The institution’s founder and longtime Detroit resident Olayami Dabls—who prefers, simply, Dabls (pronounced dabbles)—has a broad, sparkling smile and a weather-worn, distinctly Detroit demeanor. An energizing and animated speaker, Dabls mixes humor and solemnity with memorable ease, packing an anecdote with a healthy dose of insight and leaving the listener with the sense that a good story might, in fact, be all in the delivery. And the African Bead Museum is the same—when you set your eyes on the array of buildings and arrangements, you can’t help but feel more alive.

The N’kisi House (pronounced en-kiss-ee) is one of the most stunning and imposing structures of the African Bead Museum’s 18 outdoor installations. The rectangular building’s green-shingled, angled roof sits above large walls wholly awash with seemingly every color imaginable. Chunks of turquoise squeeze between pockets of sunflower yellow and marks of lime greens and lavender. But perhaps the house’s most memorable feature is the hundreds of pieces of mirrors arranged like loose tiles atop the build’s colored surface. The effect is mesmerizing.

“The N’kisi is made of iron, rock, wood and mirrors. You place a nail or a piece of iron in the house, and you ask it to do certain things for you,” Dabls explains, detailing one of the many allegories he came up with for the museum’s installations. “I asked the N’kisi to do three things for me: to not allow vandals to vandalize it, not to allow graffiti artists to tag it and not to allow the city [officials] to see it.”So far, all three of Dabls’ wishes have held true, though not without challenges along the way.

When Dabls first started the museum nearly 30 years ago, much of the country had seemingly all but written Detroit off as a post-industrial tragedy. From the decline of the auto industry and rising unemployment, to the violent unrest that marked the city in 1967, the Motor City struggled to find a sense of economic or political stability throughout the second half of the 20th century. The Detroit of Dabls’ formative years was a very segregated one. The city’s black and white residents rarely interacted, while some neighborhoods were virtually off-limits. By the time Detroit’s tension turned into turmoil in the summer of 1967, Dabls was nearing his 20s.“That was the most impactful thing to happen to me—to be part of a city at war with itself. You had one group saying, ‘Look at them tearing up their city,’ and then you had those with more information saying, ‘No, this is a rebellion,’” he recalls. “They’re rebelling because of the conditions that they’re in.”

Not long after, Dabls attended Highland Park Community College, where he became immersed in the college’s Afrocentric curriculum—a growing academic trend that gained more footing in many universities and majority-African American schools across the country. Highland Park’s academic program provided its African American students with a greater sense of the African continent beyond popular culture’s often-racist or caricatured depictions. The experience was the first of its kind for Dabls and instilled a notably strong and evidently lasting sense of pride.He eventually transferred to Wayne State University to study painting and fine art and later worked at Detroit’s first-ever African American Museum, originally named the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History.

By the time the idea for the African Bead Museum occurred to Dabls, he was nearing his 50s. He’d been studying, curating and creating art for decades, but he found himself ready to dip his hands into a new project—one that would bring all of his passions together and allow him to grow his creative career in a more authentic way.

“The first thing I was slapped in the face with was, ‘It’s gonna take money, Dabls!’” he exclaims, chuckling heartily at the memory.Not one to get bogged down in paperwork or formalities, the now-71-year-old painter’s recollection here becomes lighter on the details—and more entertaining still. Back then, he’d had his eye on the property the African Bead Museum now sits on for some time, but it took some skill and charm to get the property without spending a dime. The process of actually being legally allowed to use the land and its buildings is a storied one that, in writing now, can’t do justice to the casual drama and comedy in Dabls’ retelling. It involved a frugal but eventually generous landowner, a handshake deal, multiple signatures on a land deed and a well-connected friend.

“It was the wild, wild west in the city at that time,” says Dabls.With the property finally in hand, the next challenge was where to begin. He couldn’t afford any dramatic renovations or multi-year development plans, so he picked a wall of one of the buildings and just started painting. It was a somewhat risky move. Detroit was in the beginning stages of cracking down on graffiti artists in the city. Dabls risked having his work lumped in with theirs and subsequently removed—but ironically enough, those same artists were also his inspiration.

“At Wayne State, I studied as a studio artist. But now I had to forget about all of that because I needed a way to create an impactful image in no more than a couple of weeks,” Dabls explains. “Studio artists can spend nine months working on two or three paintings and not finish either one of them. But I needed a new way of making art, so I began to study cave drawings and [graffiti artists] in LA and New York. These guys were painting six-story buildings overnight.”

As more time passed and no word came from the city, Dabls’ confidence grew. He started experimenting with different techniques and discovered new things about how weather impacted paint and how various colors interacted with the natural light. People walking by started conversations with him wondering what he could possibly be working on—and why he’d work on it in that particular part of Detroit.“When I first said I was going to open this museum, everyone looked at me and thought I was crazy. This was a high-crime zip code; it was dilapidated—no one in their right mind would risk losing their money by opening up something here,” he says. “I didn’t see it like that.”

He was well aware of the possibility of property damage, but it wasn’t the sort of thing he put much weight on in comparison to the potential benefits of bringing his vision for the African Bead Museum to fruition.“The minute I started painting on the building, people in the community began to come by and look and comment. Some of them would say things like, ‘Why are you here? This needs to be out there where the money is.’ And I’d think, ‘Wow, people really think art is only for people with wealth.’ That’s why the people who need art the most can’t get it in their communities.”

Early on, people realized Dabls was looking for materials to recycle as decorations for the African Bead Museum, and soon after, donations started coming from all around. At this point, large portions of Detroit were still in disrepair, with many of its buildings and homes vacant and falling apart. Dabls befriended locals who’d go hunting around abandoned properties and bring him trinkets and materials to contribute to the museum’s now growing structures.

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

“If paint is donated to you, then you have the energy of the people in those paints,” Dabls explains. “Anytime you touch an object—especially if you touch it for a long period of time—you leave your energy in it, and others can come along and sense that energy. Everything that I used to build (in the African Bead Museum) was recycled.”

The communally donated source materials for the space added to its uniquely homegrown feel. As the museum began to take shape and expand, Dabls stayed connected to the people in the neighborhood. The air of inaccessibility and stuffy, elitist vibes that traditional arts institutions and museums are sometimes known for was nowhere in sight. It’s one of the aspects of the museum that Dabls is the most proud of.“We’re blazing a whole new trail when it comes to community-based museums.”

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Now nearly three decades after first opening, the African Bead Museum is on the verge of the second phase of a large multi-phase renovation project after securing considerable funding from donors in recent years. While the property is still gorgeous, some buildings are badly in need of upgrades, and other portions are near collapse. Part of the roof of one building has already caved in. A second building could use new windows, heating and updated electrical systems. Generally, the property yearns to be designed for 21st-century arts patrons, though construction needs haven’t deterred crowds of visitors. Dabls says the museum’s furthest guests have been from places like Australia, China and Russia—even Guam.

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

“I’m having fun. You know, I never knew that talking with people from all over the world had its own pleasure in it.”Indoors where the African Bead Museum’s gallery of beads is housed, he entertains people with stories and jokes, sharing information about the various traditional uses or ceremonies that specific beads might’ve been featured in. According to Dabls, some of his collection dates back hundreds of years. Rather than installing plaques or captions of information, Dabls prefers to share the history orally, in some ways mimicking the griots and oral storytellers that he learned played pivotal roles in ancient African cultures and societies.

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

That same storytelling tradition has threads all through the African Bead Museum and Dabls’ own personal artistic practice. Similarly, he prefers the title of visual storyteller to artist when asked to label himself. On the museum’s grounds, each of the outdoor installations represent stories that embody pivotal moments or lessons across centuries of human history. Heavily influenced by African folk tales, Dabls uses four main materials—iron, wood, rock and mirrors—as metaphorical tools or memorable characters to create stories about big ideas like assimilation, colonization, the importance of knowing your cultural history, conservationism and more.

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

“This place is so far past my wildest expectations,” he insists. “I just want to maintain what we have going on here—and I know those words go against what they teach you about business, but I don’t accept that. I want to maintain where we are now and for other people to copy what we’re doing now, because the world would be a better place if more people used art to heal the community as opposed to making one or two people extremely rich.”

Iron, Wood, Rock and Mirrors: The Evolution of Olayami Dabls' MBad African Bead Museum

Dabls’ voice brightens at the idea of dozens of African Bead Museums and similar venues popping up around the country, livening up neighborhoods and enthralling visitors.He teases, “I told you I was a brilliant man, didn’t I?"

Images courtesy of Attilio D'Agostino.

This story originally appeared in ALIVE Volume 18, Issue 3.

.